Does Location Impact Creativity?

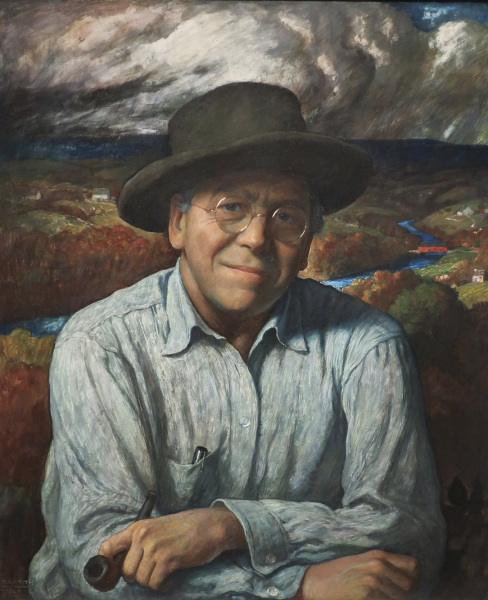

For years I saw photos of the great Palladian window on the north wall of illustrator, N.C. Wyeth’s studio, and somehow I was drawn to it. It’s so powerful – so dramatic. N.C. Wyeth’s personal touches to the architecture and choice of setting for his studio impacted his creativity. The surroundings connected with him on a deep level according to his letters.

Among those misty gray hills of Chadds Ford, along those stretches of succulent meadows with their stretches of peaceful cattle and those big sad trees, and the quaint and humble stone farmhouses tucked underneath them, there is that spirit that exactly appeals to the deepest appreciation of my soul. To me, it is like wonderfully, soft, and liquid music. ~N. C. Wyeth, letter to family, 1925

It affirms the concept that “where” one creates art matters. The energy in a particular setting or landscape can ignite creativity on such a deep that the connection between artist and surroundings becomes completely fluid. One feeds the other.

N.C. Wyeth was famous for his illustrations in early 20th-century books like Treasure Island, The Black Arrow, and Last of the Mohicans. He was also the father of Andrew Wyeth and the grandfather of Jamie Wyeth.

I knew about N. C. Wyeth and his illustrations, but I wasn’t nearly as attracted to his work as I was to his son Andrew’s. But when I first saw images of that studio on a PBS documentary, I had to find out more about the man who built it. It has a charism about it – a draw – something unique unto itself. This comes through even in pictures.

Does “where” an artist creates the art matter? I’ve asked so many artists that question. The answer is always “yes” and that isn’t surprising. But hearing the artists’ answers … that’s the amazing part. Every answer is unique – and listening to them try to describe the impact of that ephemeral pull – that connection to place and what it does to their creativity presents the artist at human level devoid of any ego trappings. The answers are raw and personal.

I’ve asked the question of musician Paddy Maloney of the Chieftains, the actor John Hurt, the Irish painter Carol Cronin, and World Champion Waterfowl carver Rich Smoker – and all of them had to think. No one answered quickly – but they all answered in the affirmative and continued on a deeply personal level. (these are stories for other blog post).

According to N. C. Wyeth, in letters he wrote – the locality absolutely matters. While it’s true that an artist – especially a landscape artist – may not be out in the landscape during the creation of the actual art piece … the pull and soul of that landscape – especially if it’s in close proximity – still sits somewhere inside the creative mind of the artist – still providing that connection – even at a distance.

N. C. Wyeth wrote about walking out into the landscape and just letting himself absorb his surroundings to nourish the creative spirit – and then returning to the studio to put brush to canvas.

It turns out that his own creativity manifested itself in exponential proportions in that little white building on the hill. It was there that N.C. Wyeth churned out hundreds of illustrations for books and magazines that captured the imaginations of children and adults alike in the first part of the twentieth century. It was also the place where N.C. nurtured the artistic talents of his five children – four of whom became artists – three fine artists and one a music composer.

It was in that home and studio that he entertained other artists and prominent people of the day – including the three artists that married his daughters. And finally, it was the N. C. Wyeth Studio where his daughter (and artist), Carolyn Wyeth operated an art school that trained and mentored the likes of her internationally recognized nephew – Jamie Wyeth (Andrew Wyeth’s son), and Chadds Ford artist, Karl J. Kuerner whose family and farm were subjects of many Andrew Wyeth paintings.

In 1984, a rendering of the N.C. Wyeth Studio (painted by his son, Andrew) earned a place on a US Postage Stamp in a grouping that highlighted the contributions of Andrew Wyeth. The painting was entitled “North Light” (pictured above). That rendering also became the focus of a Christmas ornament released by the Brandywine River Museum of Art which currently owns and operates tours to both the N.C. Wyeth House and Studio and Andrew Wyeth’s Studio.

Who Was N. C. Wyeth

He was born in Massachusetts in 1882 but later moved to Chadds Ford, PA to study under the illustrator Howard Pyle who had a school there. By the early 1900s, Wyeth was producing magazine and book covers for notable publications. He got married and started a family there in Chadds Ford, and by 1911 he had earned enough from the illustrations of the book Treasure Island to purchase 18 acres of land on a hill overlooking the Brandywine Valley.

It was there on that piece of land that N.C. Wyeth built his home where he raised his five children – four of whom became artists. And 25 steps away from the front door of his home, he built his studio. It was in that studio that he created the majority of his work, and it was there that he mentored and trained many artists including three of his children – Andrew, Henriette, and Carolyn.

N.C. Wyeth Mural Studio

In 1923, N.C. Wyeth added a mural studio to the existing building. It had a wall of north windows – Wyeth believed that northern light was the truest light – that extended into the bend of the roof, similar to greenhouse windows. He had a stairway with platforms built right up to the ceiling, allowing him to paint huge murals depicting his illustrations.

There was no reason for publication that the canvases had to be this big. I think it’s sort of indicative of the energy he wanted to put into these images.”

~Christine Podmaniczky, Curator of the N.C. Wyeth Collections at the Brandywine River Museum

N.C. Wyeth stated again and again that the artist had to connect his emotions to the art… the creation had to be an emotional experience. Andrew Wyeth is quoted many times saying the same thing. N.C. would have classical music playing while working on a painting. His daughter Carolyn said that her father did everything in a BIG way. Everything he did was over the top.

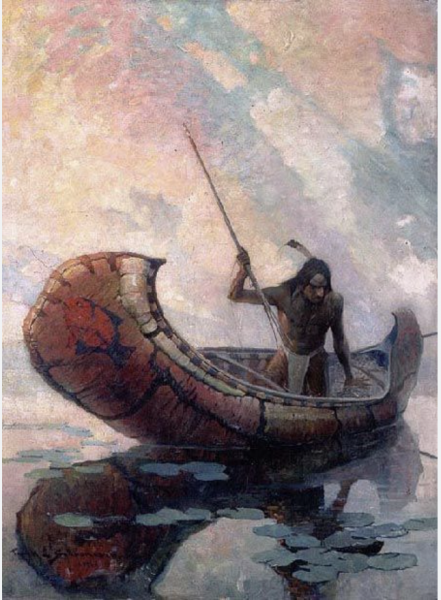

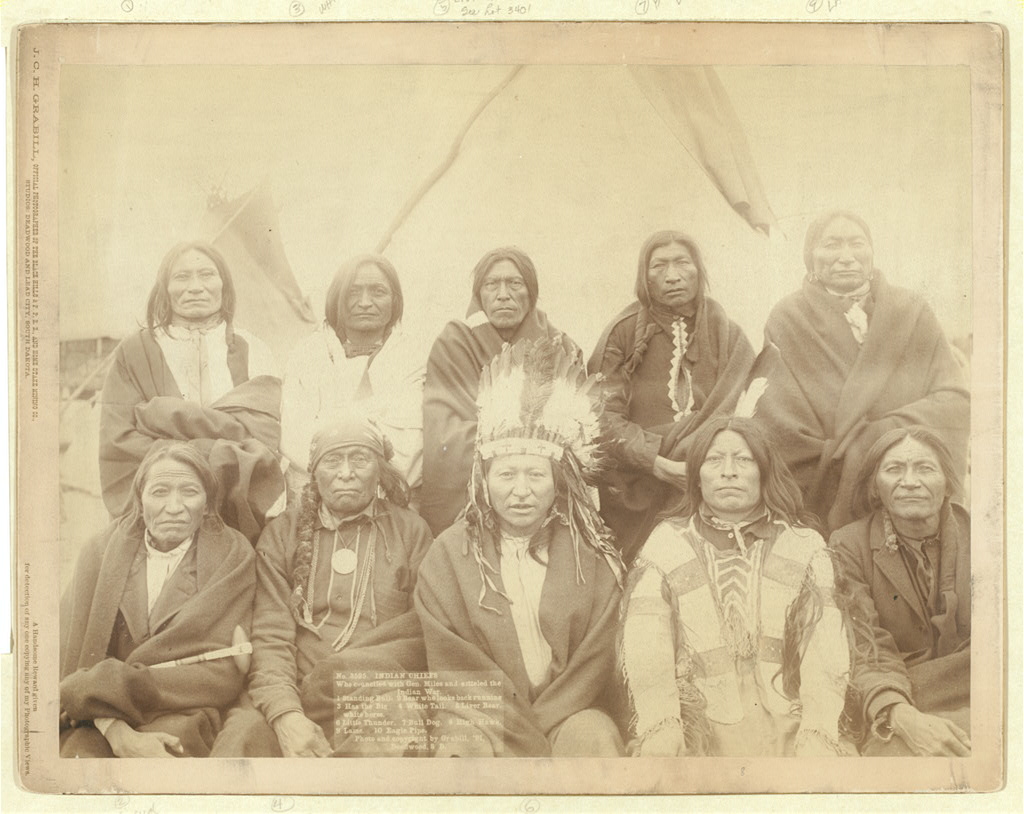

The studios were full of props – cutlasses, costumes, guns, hats, bottles, model ships, and over 900 books. One of the rarest props is an early 19th-century birchbark canoe crafted by the Penobscot tribe in Maine. N.C. purchased it in Maine and had it brought by train to Chadds Ford. It hung from the rafters of the studio when N.C. was alive.

Like Father, Like Son, Like Grandson

N.C., Andrew, and Jaime painted in two home places

N.C. purchased a summer home for the family near Rockland, Maine, and the family spent summers there. It was during one of these visits that Andrew Wyeth met his future wife, Betsy. It was also where Andrew met the Olson family – Christian and Alvaro whose faces and home place are featured in so many Andrew Wyeth works including his most famous work, Christina’s World. These two landscapes – Maine and Chadds Ford were the only two places that N.C. and his son Andrew painted. They didn’t travel the world, though they had the means. They were inspired – if not tied to – those landscapes. And Jamie who is a current working artist has also adopted these two home places, never straying far from either.

I don’t believe that any man who ever painted a great big picture did so by wandering from one place to another searching for interesting material. By the gods, there’s almost an inexhaustible supply of subjects right around my back door, meager as it is. I’ve come to the full conclusion that a man can only paint that which he knows intimately. He’s got to know it spiritually – to do that he’s got to live around it and be a part of it.

– N.C. Wyeth, letter to family, 1935

N.C. Wyeth’s Emotional Struggles

N.C.’s son Andrew once said of this father, “He wasn’t selfish enough to be a true artist.” Andrew was referring to N.C.’s melancholy over being an illustrator, painting to the contract for an income, rather than being a fine artist – painting from emotion. N.C. writes about this personal struggle over and over in letters to friends and family. The selfishness Andrew was referring to was about putting himself before everything else and focusing only on the painting. N.C. adored his children and his family and he spent so much of his time making a life for them, reading to them, teaching them, expanding their creative minds, and making homes for them. He would have had to lose that balance between work, family, and the passion for creativity if he’d put his entire self into the art.

But throughout his life in the Brandywine Valley, he clung to the landscape. His belief was that the landscape surrounding the artist as he or she creates has a direct connection to the work produced. It comes through in a few lines from a letter he wrote about the landscape surrounding his home and studio.

By the early 1940s, N.C. letters were becoming dark. They indicate possible depression. The last painting N.C. completed features a Chadds Ford farmer standing at a fence as the night begins to fall. His little girl is by his side though her face is turned away from view – looking at the farmhouse in the distance where there is one single light lit in a second-floor window. The farmer’s wife was dying of cancer and her presence is represented by that light. The emotion of the painting is so palpable. When I saw the original (entitled “Nightfall”) at the Brandywine River Museum I was so moved by it. My husband had recently passed away – in our home, and I could so relate to the feeling of impending loss – of home being a safe place to die, of the absence about to manifest itself – of nightfall – the end of the light. I bought a copy of the print and it hangs near my kitchen fireplace. I love it.

On October 19, 1945, N.C. Wyeth just three days shy of 63 birthday, and his three-year-old grandson were tragically killed when their stalled station wagon was hit by a train. Their deaths were instant. It happened mere miles from the home and studio where N.C. Wyeth raised his family, created hundreds of works of art, inspired so many aspiring artists, and created a legacy for artists still practicing in the Brandywine Valley.

On that day her father was killed, Carolyn Wyeth went into his studio and laid out N.C.’s brushes on his artists’ palette. She wrote in pencil on the palette

October 18th was the last day N.C. Wyeth used that palette. It still sits on a table in his studio today… just as he left it.

DO NOT USE

October 18, 1945

N.C. Wyeth

Chadds Ford, PA

Laurel Riegel

December 16, 2025The mural on display in NC Wyeth’s studio is the original mural painted in 1934 and entitled, William Penn: man of vision, courage, action. It is not an illustration of John Paul Jones.

Mindie Burgoyne

December 17, 2025Thank you, Laurel for that correction. I’ve made a notation in the caption. Also, thank you for visiting the site.